Vergulde Draeck

Vergulde Draeck (1656)

Background to the loss

On 4 October 1655 the Vergulde Draeck of the Amsterdam Chamber of the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) set sail from Texel, on what was to be her second and final voyage to Batavia (modern Jakarta) in the East Indies. Her master was Pieter Albertsz and she had a crew of about 193 men, indicating a medium size East Indiaman (she was occasionally referred to in contemporary texts as a yacht). It is recorded that she carried a cargo of trade goods worth 106,400 fl. together with eight chests of silver coin worth 78,600 fl. After stopping briefly at the Cape of Good Hope, she sailed east following the route to the East Indies established by Henrik Brouwer in 1611. This course followed the Roaring Forties east towards the Southland, and then north to Batavia. On 28 April 1656, the Vergulde Draeck struck a reef close to the Southland at the beginning of the first day watch, at a latitude 31 ° 16'. Seventy five survivors including the Master and Understeersman reached shore, and all that could be saved from the ship were a few pro visions. The Master, Albertsz, dispatched the Understeersman and six men to obtain assistance from Batavia. The Master, Albertsz sent the Under steersman in command of six men, who arrived at Batavia on 7 June 1656, 40 days after the Vergulde Draeck had been wrecked. The Commander and Council of the VOC at Batavia acted promptly. The day after the news of the wreck, a yacht, the Goede Hoop and the flute, the Witte Valk were dispatched to the Southland to search for the wreck and the survivors. The Witte Valk was unable to approach land because of rough seas, and four months later returned to Batavia having found no trace of the survivors. The Goede Hoop, however, searched some distance of the coast line and at one point made a landing, which in the events that followed cost the lives of 11 of the crew. She returned one month after the Witte Valk on 14 October 1656, also having found no trace of the Vergulde Draeck or the survivors. Thus this initial search had been totally unsuccessful. A year later, following recommendations from Batavia to the Commander Jan van Riebeeck, of the VOC settlement at the Cape of Good Hope, a further expedition to search for the Vergulde Draeck was mounted. This time the small flute or flyboat the Vinck, outward bound to Batavia, was instructed to call at the Southland and search for survivors. Once again the expedition failed to find any trace of the wreck or survivors (possibly because of the inclement weather and the fact that the first landfall on the Southland was made too far to the north at 20° 07’). The Vinck sailed north along the coast and arrived at Batavia on 27 June 1657.

By the end of 1657, the company at Batavia held little hope for the survivors of the Vergulde Draeck. Nevertheless, on the slim chance that someone might still be alive, a third expedition was mounted. Two galliots, the Wackende Boey with a crew of 40 and the Emeloort with a crew of 25, were provisioned for six months. Strict sailing instructions and a code of behaviour were issued, together with orders to chart the coast of the then relatively unknown Southland, and investigate possible trading contacts. Orders were given that a proportion of any money re covered from the salvage of the wreck would be given to the crew as a financial incentive to encourage them in every possible way. It seems, however, that the motives of VOC were more than purely financial, since in the orders it is recounted: ‘…that it is our opinion that this will not happen (the recovery of the money) in view of the great peril and dangers and since human life we deem more precious…’ On New Year’s Day 1658 Skipper Auck Pieters Jonck, Master of the Emeloort, and Skipper Samuel Volkersen, Master of the Wackende Boey, set sail for the Southland. By 2 February the Skipper and merchant of the Wackende Boey were complaining that the Emeloort was not sailing fast enough, a week later when the Emeloort tacked to the south firing a cannon and raising a light in the mizzen shrouds, the Wackende Boey sailed on, and from this point the two ships appeared to have acted independently, although they met up on several occasions on the coast of the Southland. The Emeloort sighted the Southland at sunset on 24 February at about latitude 33° 12'. From this point she sailed north along the coast, carrying out soundings and constructing a chart of the Southland. On 8 March at about 30° 25' a fire was seen on land which, on firing signal guns, was answered by another fire. The following day after further signals and replies, a boat was sent ashore, however, on arriving at the beach the fires were extinguished, and as it was late, the boat returned. The following day the ship’s boat was again dispatched and this time made a landing. It appears that aborigines were responsible for the fires, as the search party met up with a group and described their primitive habitation; however, neither traces of the survivors nor wreckage was discovered. The Emeloort after cruising in this general area, departed for Batavia, arriving there on 18 March 1658. The Wackende Boey first sighted the Southland at 09.00 hrs on the morning of 23 February at latitude 31 ° 40' and charted the island now known as Rottnest. A landing was made on the 24th at 31° 20‘ where wreckage of what was thought to be the Vergulde Draeck was found. On the 27th and 28th further landings were made at 31° 14' and 30° 40' but no wreckage was sighted. On 18 March the ship anchored on the north coast of Rottnest, the island was explored and it is recorded that the ship was scraped below the waterline. On the 20th after sailing north and making a landing at 31 ° 09' a beam from the Vergulde Draeck was recovered. A second landing was made and more wreckage was found. On the evening of the 22nd as Volkersen recounts ‘... Since it was very fine lovely weather…’ the boat was sent ashore again. During the night a SSW gale blew up and on the following day it was assumed that, as the boat had not returned, it must have sunk (sic). The ship then managed, with great difficulty, to beat off the lee shore and make for the open sea. Five days later the Wackende Boey again passed the spot where the boat with 14 men, including the Uppersteersman, had last been seen, firing signal guns to no avail. It was then decided to sail on to Batavia as it was assumed that the boat and crew were lost, presumed drowned.

At dusk on 28 March a fire was seen on shore and on firing a signal gun another fire was lit. This was assumed to be ‘the work of Christians’ either of the ship’s boat or the survivors of the Vergulde Draeck, presumably because it was different from other fires so far sighted. The ship hove to during the night; they could not land as they had neither boat nor gig and the site was not a suitable anchorage. In the morning the ship was found to have drifted to the north, and it appears she continued on to Batavia without investigating these signals, which must have been significant since they ‘had never observed such a fire before…’ This fire was quite clearly, from the records of Uppersteersman Abraham Leeman van Santwigh, the one that he and crew of the boat had lit. On 10 April 1658 the Wackende Boey arrived at Batavia, having left 14 men behind, under very dubious circumstances, and indicating, on a superficial examination of the records, gross negligence on the part of Volkersen. From the journal of Abraham Leeman for the evening of 22 March (the day of the loss of the boat), we find a difference in opinion over the weather conditions between the Master Volkersen: ‘very fine lovely weather’ and the Uppersteersman Leeman: ‘the sea is rising so fast ashore that I am afraid for bad weather’. In spite of Leeman’s warning the Master again sent him ashore (the second time that day). Being unable to land because of the SSW gale, the boat anchored for the night. In the morning because of the strong winds the boat ran before the wind, lost her rudder and could only be roughly steered with the oars. Eventually the boat was cast over a reef and swamped, luckily escaping major structural damage. After repairing the boat and collecting seal’s meat and water they continued sailing along the coast. On the 28th, the Wackende Boey was sighted, and a signal fire was lit. A cannon was then fired from the ship which was answered on shore with a second fire. Thus the description of the events on the shore by Leeman exactly tallies with Volkersen’s journal, so there is no doubt that this is the same event. Due to bad weather Leeman could not put out in the boat, so that in the morning, as recorded above, the ship was gone. Leeman and the boat’s crew remained at that spot for 11 days hoping that the Wackende Boey would return. On 8 April they set sail for Batavia with provisions of seal’s meat, sea-weed and ten gallons of drinking water. On the journey three crew died of thirst and for 15 to 16 days before reaching Java they had been forced to drink seawater and their own urine. On reaching the coast of Java five men were sent ashore to collect food and water to re-provision the boat, but having satisfied their own needs with food and water, they refused to do any more. A total of seven crew that were able to swim were sent ashore and they all acted in a similar manner. As the weather conditions deteriorated in the after noon Leeman decided to depart. It is truly remarkable that Leeman and the three remaining crew did not abandon the boat and thus alleviate their thirst and hunger.

The following day (30 April) the boat was wrecked in the surf some miles along the coast, due to the exhausted state of the crew and their depleted numbers. After struggling through the Javanese jungle, these four men eventually arrived in Batavia on 23 September 1658, 185 days after being marooned on the South land, a truly remarkable feat of endurance, courage and determination. The masters of the Emeloort and Wackende Boey were ordered to be examined by the High Fiscal of India, since they had disobeyed the sailing instructions and Volkersen had deserted 14 of his crew in dubious circum stances. It was assumed at this point that there was almost no hope that the survivors of the Vergulde Draeck could still be alive. However, it is interesting to note in the correspondence from Batavia that it was left to the discretion of the Heeren XVII (the Directors of the VOC in the Netherlands) to issue instructions for a galliot to call in at the Southland ‘in case anybody can be found’. In fact no further expeditions were mounted, although the Elburg, commanded by Jacob Pieterszoon Peereboom, touched at the south-west coast of the South land in 1658 at latitude 31° 30' S.

Events leading to the discovery

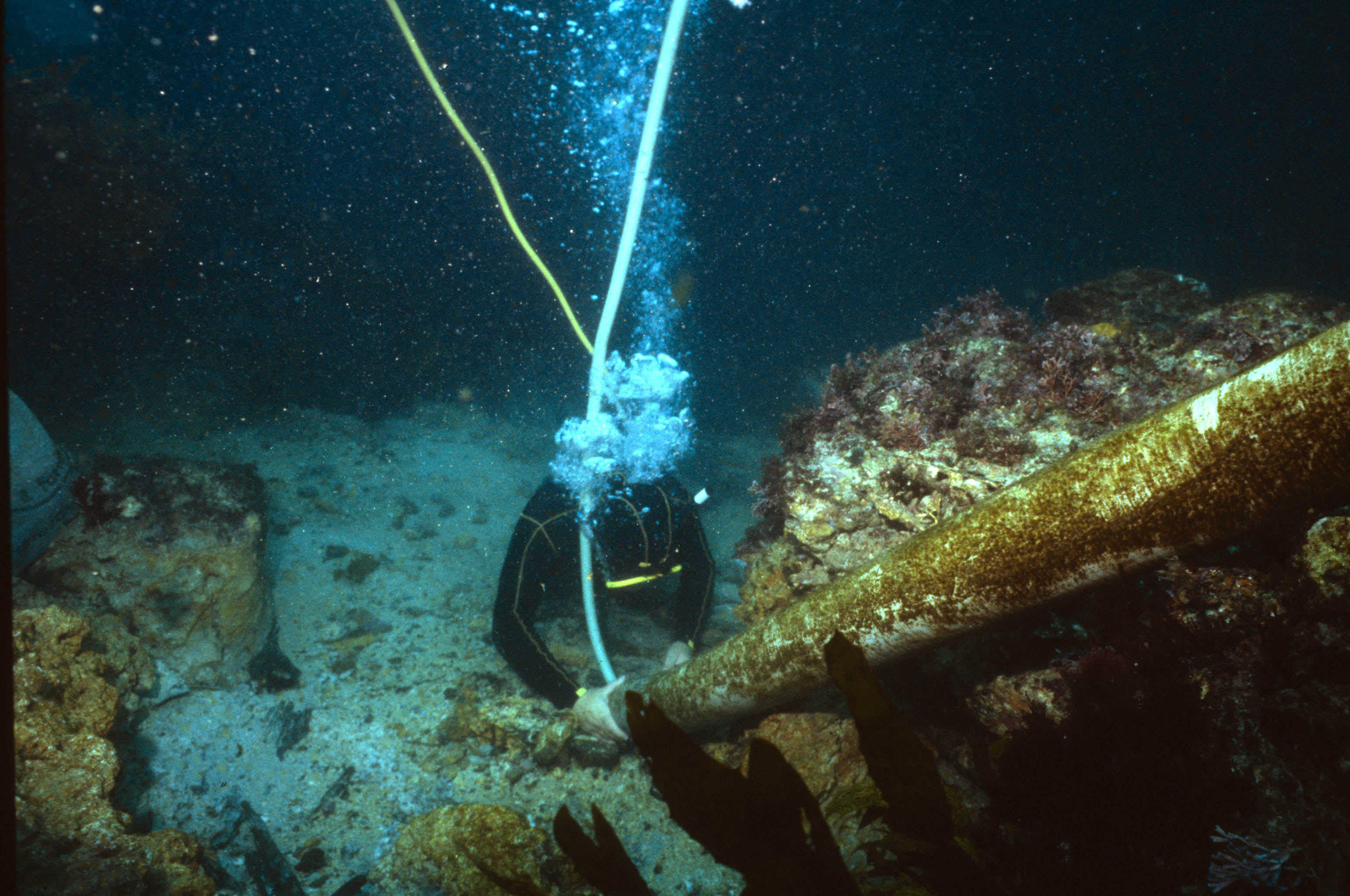

For nearly 200 years the documents relating to the Vergulde Draeck remained in the State Archives in Holland. In the intervening years, the Southland had been explored and by the early 19th century the British had started to settle the continent. One of the settlements was the Swan River Colony, on the coast of Western Australia, only about 120 km south of the wreck of the Vergulde Draeck. The publications of Major (1859) and Heeres (1899) in English stimulated much speculation as to the position of the wreck of the Vergulde Draeck. In 1931, a young boy, A. Edwards, found about 40 silver coins in the sand-hills just north of Cape Leschenault (31° 19’). These coins caused much excitement at the time as their dates ranged between 1619 and 1655, thus indicating that they could belong to the survivors of the Vergulde Draeck. The coins consisted of about 24 Mameita-Gins, a Japanese coin of the Keicho period (1601 to 1685, probably prior to 1650) and about 16 Ducatons and half Ducatons of the Spanish Nether lands ranging from 1637 to 1655. The first substantiated report of the discovery of the wreck of the Vergulde Draeck came on 13 April 1963. A group of skin divers from Perth were spear-fishing on a reef about 12 km south of Ledge Point when the remains of a wreck were sighted. A superficial examination of the site revealed cannons, anchors, ballast bricks and elephant tusks, thus clearly indicating an old wreck, and possibly the Vergulde Draeck.